Editors Note

Work in progress. Last update was 3/28/2025.

This is an undergrad research paper, do not expect a lot.

This is a paper that was written for the department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences at the University of Michigan, also known as NERS.

I’m uploading this to my website to perserve it in another location other than personal devices or some random cloud server.

This was taken from a PDF and painstakingly converted to a markdown file line by line by me, so if anything seems off that is why!

You can contact me at nickstambaugh@proton.me for any inquiries or questions.

Making Nuclear Energy Cost Competitive with Fossil Fuels and Renewables

August 2021

| Author | Contact |

|---|---|

| Isaac Reichow | reichowi@umich.edu |

| Nick Stambaugh | stambaun@mail.gvsu.edu (editor) |

| Syhming Vong | vongs@mail.gvsu.edu |

Index

CARB - California Air Resources Board. The regulating body in California that oversees the distribution of allowances for carbon dioxide emissions.

Cap and Trade - A system to limit the amount of emissions from a business. The key is that organizations who do not emit can sell their ‘emission credits’ to the businesses who do want to emit, thus incentivizing less emissions since it raises the cost to emit and brings emitting into the open market at a price.

Capital Costs - A fixed expense in which land, buildings, construction, machinery is purchased one-time for the purpose of production.

CCS - Carbon capture and storage, a large capital-intensive cost that maintains and captures carbon emissions from fossil fuel energy production. Also referred to as CCUS.

DOE - Department of Energy, an agency enacted by Congress and the United States government to assist in assessing and implementing energy policy.

EDF - Électricité de France, French multinational energy company who mainly focuses on nuclear.

FOAK - First of a kind. The first reactors built for any new type of technology.

IEA - International Energy Agency, an organization that analyzes global electricity generation and consumption. It also compares countries’ policies and actions regarding climate change.

ITC - Subsidy that is called an Investment Tax Credits which incentivizes investment in new technology by offering tax credit for that specific investment.

LCOE - Levelized Cost of Electricity is an economic metric that gauges the cost of investment in a powerplant over the plant’s lifetime generation of electricity. This is frequently used by investors and policymakers to decide if a project is economically viable over the plant’s lifetime.

LWR AND PWR - Currently these are the reactor types that are deployed commercially in the United States. They are large, expensive construction projects which take roughly 7-10 years to build. Despite large upfront costs, increasing ROI is expected as the plant takes on upgrades. LWR stands for light water reactor and PWR is a pressurized water reactor and a type of light water reactor.

NRA - Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority. Analogous to the U.S.’s NRC.

NRC - Nuclear Regulatory Commission, an agency enacted by Congress and the United States government to oversee the licensing and regulation of nuclear power plants.

Paris Climate Agreement - This is an international legally binding treaty with 195 signatories which seeks to reduce the harmful effects of CO2 emissions by forcing economic change within countries across the world. Notably, the USA, China, Russia, and the bulk of the EU have signed.

PTC - Subsidy that is called a Production Tax Credits which incentivizes production of a certain commodity by offering tax credit for that production.

PV - Photovoltaics, the technology that converts sunlight or the sun’s radiation into electricity, widely used within solar panels for the purpose of transferring light/heat from the sun into useable electricity to consumers.

R&D - Research and development.

ROI - Return on investment, or the rate at which cash is received via investment costs. A ratio that is used by businesses and governments to gauge the economic viability and profitability of a given project.

SMR - Small Modular Reactors, small reactors which can be produced in factories for a fraction of the cost and size of current nuclear plants (LWR and PWR). New designs seek to increase safety features and lower construction times, which address the big issue of cost overruns in nuclear power.

Subsidies - Governmental incentivization to invest in or expand certain economic sectors. The goal of a subsidy at a fundamental economics level is to increase either supply or demand.

SWOT - acronym for Strength, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats. Used in business to gauge multiple aspects of a company and how the strengths and opportunities can overcome the weaknesses and threats to the organization.

TCC - Total Capital Cost. This comprises materials and labor for construction, a decommissioning fund and financing.

Abstract

Climate change will have a devastating impact on our planet’s ecosystem and its inhabitants. Many changes need to be made across economic sectors with the United States to address this issue.

It is time for policymakers to take immediate action towards a clean energy future, which is an investment in the health of our citizens and youth.

Urgency is required for new policies that will change the landscape for new investments and upgrades to our aging electricity infrastructure across economic sectors.

For energy production in the United States, it is key that we shift our resources and new investments away from fossil fuel sources such as coal and natural gas. By making new and current large-scale nuclear projects economically viable again in the United States, we can help meet our goals set with the Paris Climate Agreement and lead the world in clean energy production, with the help of other energy sources labeled as renewable or green.

Within our paper, we hope to address some economic concerns with nuclear production for energy usage and to make it clear the path that needs to be taken in order to make commercial nuclear flourish much as it did in the 60s and 70s.

Since the major nuclear reactor accidents like Three Mile Island and Fukushima, public support for nuclear power is not at the levels it should be with respect to having zero carbon-emitting electricity generation, we hope this paper can garnish more support from our local communities for nuclear projects, or any community for that matter.

The United States desperately needs a major shift towards a carbon-free power source and right now it is coal production shifting to natural gas production, which is better, but not free of emissions entirely during production like nuclear.

By using nuclear as a major energy source, the United States could set itself up for further energy independence in the future, as nuclear plants can be in production for 70-80 years and that is accomplished with dated technology.

We will analyze how the U.S. government must shift its strategy in energy policy via regulations or subsidies, as well as the methods used to guide decision-making, which is analyzed by comparing the U.S. nuclear market to France’s and Japan’s. For example, in Table 4.5, we see that Japan’s NRA (similar to USA’s NRC) works closely with the construction companies in the nuclear industry and they were able to produce full new nuclear power plants in 4 to 4.5 years.

On top of that, by assessing the policy that can be deployed specifically on nuclear energy production, we can observe how the new policy will influence the capital cost in new construction. Higher carbon prices and ITC/PTC subsidies can make or break nuclear energy as a power source, and will also lay the ground working for how our country tackles climate change.

New policy or adjustments to current policy could propel our country towards a clean energy future. This paper will cover what changes need to be made to the policy with regards to nuclear energy production in the United States.

Introduction

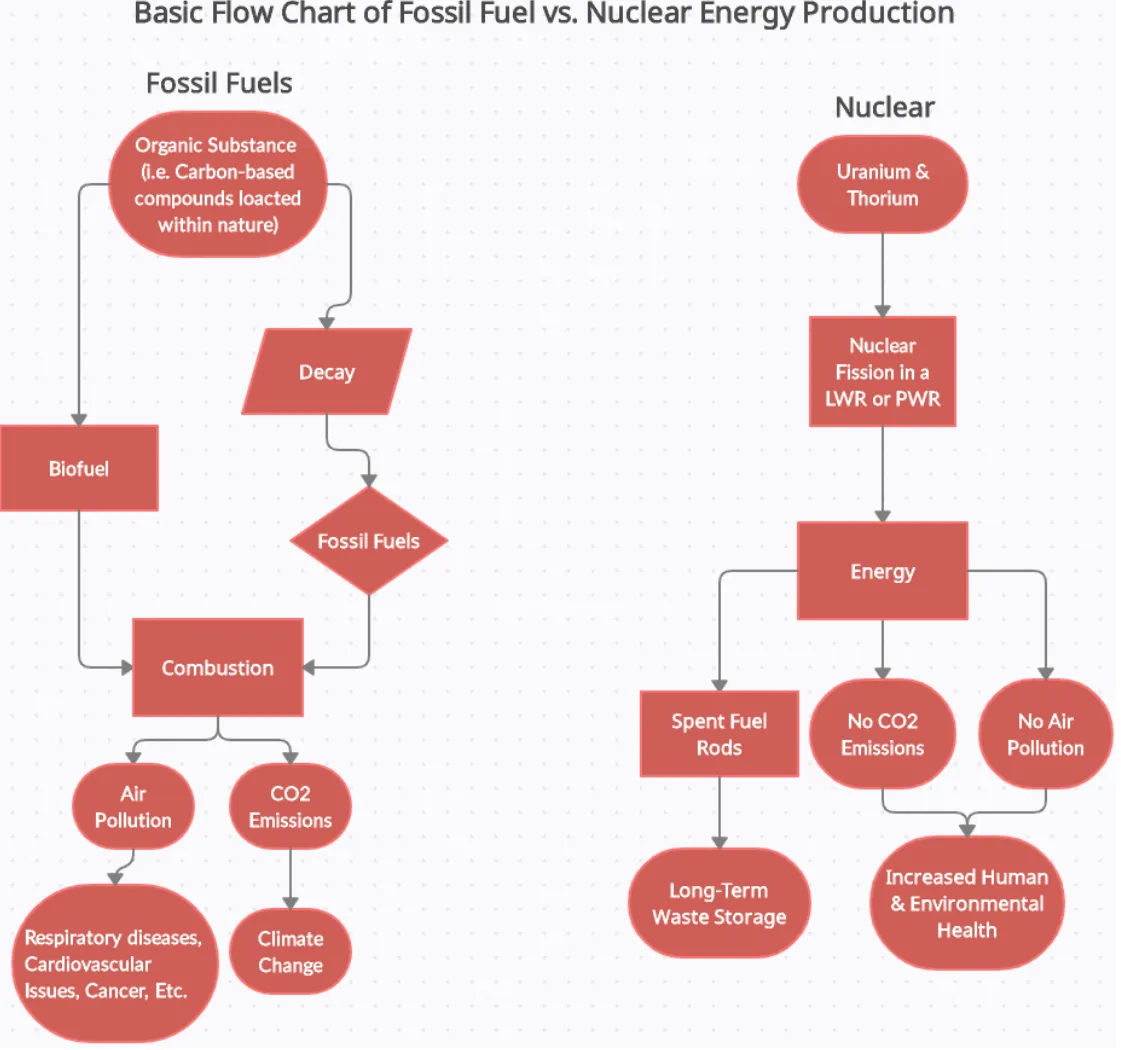

Figure 1.1

By understanding the fundamentals of how energy production works between these two sources, we can

deepen the baseline knowledge for the general public. Public trust within nuclear energy needs to be

deepened in order for the necessary changes to be made to our overall economy in accordance with the

Paris Climate Agreement.

By understanding the fundamentals of how energy production works between these two sources, we can

deepen the baseline knowledge for the general public. Public trust within nuclear energy needs to be

deepened in order for the necessary changes to be made to our overall economy in accordance with the

Paris Climate Agreement.

Public support of new nuclear tech which can operate as a separate baseload technology is vital for nuclear’s growth and sustainment in America. Within the flowchart in Figure 1.1, we can see a breakdown of how energy is produced via carbon-based organic material on the left and by nuclear fuel, Uranium & Thorium.

On the fossil fuel side, the negative impacts of combustion from biofuels (for example, ethanol or gasoline in our cars) and fossil fuels have detrimental impacts on human health and the environment. The negative effects of the combustion of carbon-based substances can be broken into two main categories. Air pollution includes ash and chemicals such as nitrogen dioxide from energy production.

Carbon dioxide release is separated into its category since the environmental impacts referred to as “climate change” from this practice have been thoroughly studied across many different academic focuses, with commonalities being found of the negative impacts from its release into the atmosphere.

On the right, we see the process of energy production from fission which leads to different results than combustion. A large downside of nuclear which is discussed briefly in this paper is the long-term waste storage of spent fuel rods.

New techniques of fuel storage are being innovated, such as the long-term plan in Finland which seeks to store spent fuel rods underground for thousands of years with no impact on the environment (Gil, 2020). Storing waste underground is safe since the waste is stored in highly engineered caskets under the biosphere, underneath any organic material.

The caskets are designed to stop the movement of radiation for thousands of years (World Nuclear Association, n.d.). The positives from nuclear energy production largely outweigh this negative since the negative externalities associated with nuclear energy production are not tied to human and environmental collapse in the same ways fossil fuels are.

Another negative to consider would-be nuclear weapon proliferation. It is certainly tied to nuclear energy production since investments in nuclear infrastructure for the purpose of energy can backbone weapons manufacturing. With that being said, the long-term effects of this are unknown and are hard to examine through the lens of economic analysis since nuclear weapons have only been deployed twice in warfare (United Nations, n.d.).

Despite the positives of production outweighing the negative externalities to many, this does not stop unnecessary shutdowns due to political reasons from occurring.

Just recently as this year, the Indian Point nuclear plant in New York was shut down with reports claiming “Gov. Andrew Cuomo and others who fought for its shutdown argue any benefits from the plant are eclipsed by the nightmare prospect of a major nuclear accident or a terror strike 25 miles (40 kilometers) north of the city (Hill, 2021).” These claims by the governor have been echoed throughout nuclear’s lifetime as a power source in America with the argument always staying the same: of what COULD happen. The media perpetuates this fear, by using language such as ‘nightmare’.

Shutting down a plant due to the prospect of an accident or terrorist attack implies a city’s leadership failed to implement necessary policies which address these issues or make plans to solve them.

Nuclear plants may be a high-value target for a terrorist attack but that is unlikely to happen since the number of terrorist attacks has decreased in the United States since the late ’90s and early ’80s (Our World In Data, n.d.).

Instead of attempting to hedge on the uncertain, we should focus on building up our systems which we are certain can work.

Nuclear plants are forced to invest highly into robust safety features meant to mitigate damages that occur if such an event were to happen, which have increased significantly following the terrorist attacks of 9/11 (United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, n.d.).

More tangible issues that are grounded in reality, like climate change, can be improved upon by keeping nuclear plants up and running. On top of this, climate change has been projected out, whereas terrorist attacks are not. This just means that there is no excuse for not fighting climate change, whereas a terrorist attack is more difficult to prepare for, although still highly important.

Many conclusions have been made that nuclear will help combat climate change and closing existing plants hurts our climate even more (Nuclear Energy Institute, n.d.). Yet the irrational fear towards an event that may or may not occur leads us to believe there is more behind the decision of closing Indian Point that has less to do with accidents and more to do with politics. Overall, the side-by-side comparison of these two flowcharts should provide insight into how different practices within energy production can lead to vastly divergent outcomes.

It highlights how human life, in general, seeks to gain from electricity production. Despite this, fossil fuel companies causing large-scale harm in the form of air pollution and climate change, the ulterior motives of those continuing to fund fossil fuels must be brought into the light, as well as making public the balance sheet of anyone involved in fossil fuel production, transparency is key to understanding how we can effectively change policy. This flowchart should make us ask ourselves if wide-spread combustion is worth it for any reason when alternatives can be created, and clearly points out how nuclear energy can contribute to society in a positive manner while helping reach the goals set out by the Paris Climate Agreement.

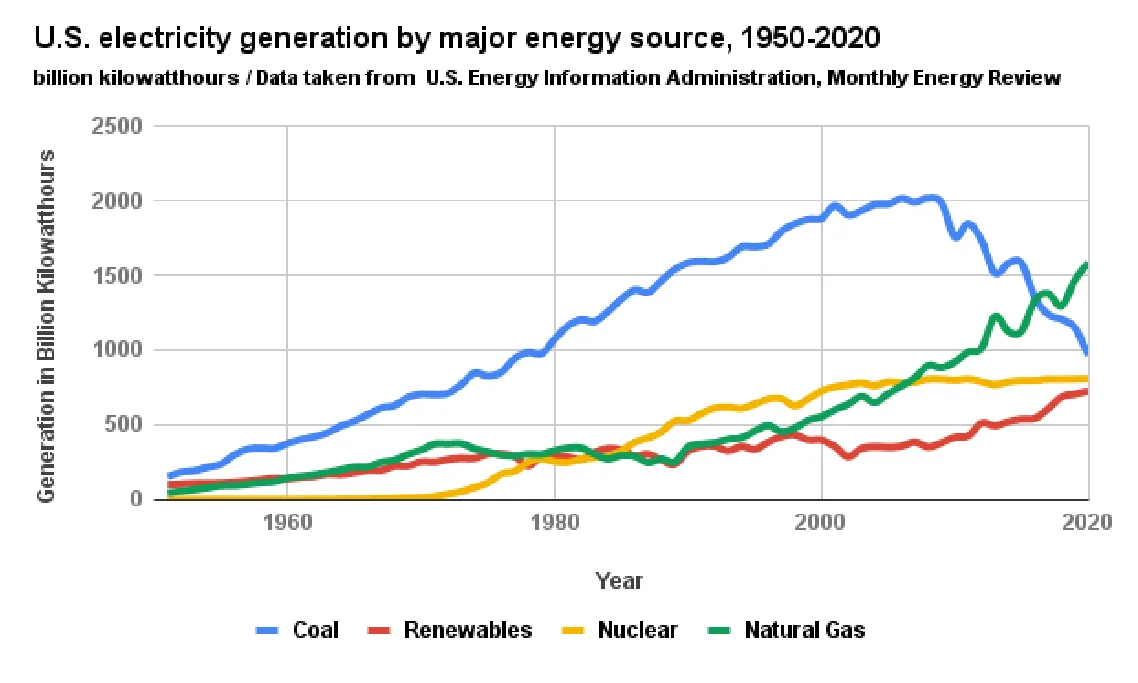

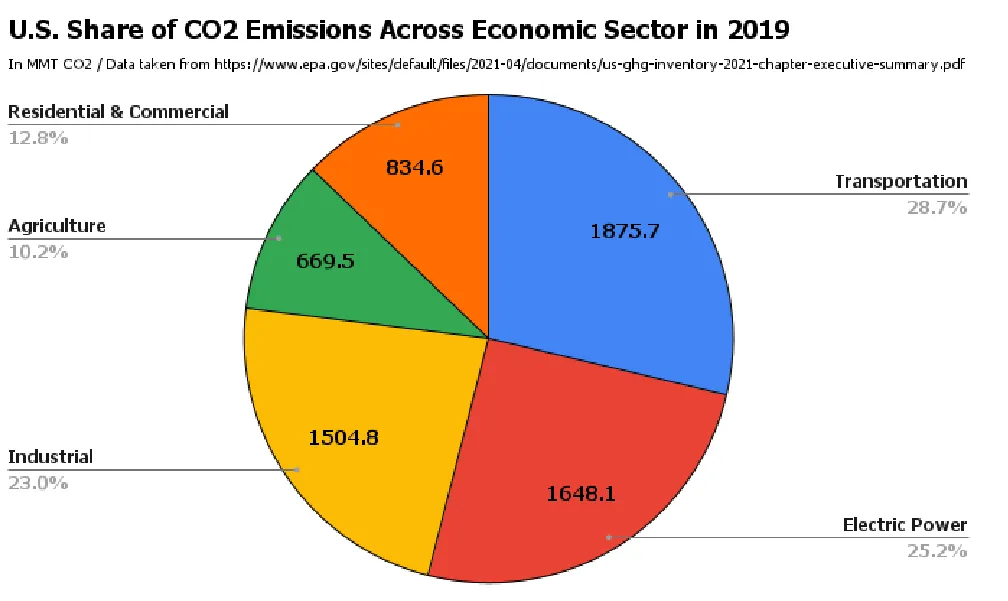

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.3

In general, according to Figure 1.3, the United States’ overall energy generation has been dominated by coal and natural gas. The total generation using coal surpassed 2,000 billion kilowatt-hours by 2005, proving the U.S. had a major reliance on coal going into the mid-2000s, with a sharp decline roughly 5 years later, showing a massive change in the U.S. energy mix, as energy sources such as natural gas begin heavily taking off around the same time.

According to Figure 1.2, the upwards trend of natural gas is explained, as we see that 2020 was a strong year for natural gas production, holding 44.6% of generation throughout that year.

Figure 1.2 also shows that renewables have just about caught up to nuclear in terms of total generation. This is backed up by the pie chart in Figure 1.3, as we can see renewables (PV, Solar thermal, on-shore and off-shore wind) shared +7.7% more of the capacity throughout the year compared to nuclear, meaning the surpassing of total generation should happen within the next couple years.

While natural gas seeks to replace coal as the dominant power source, renewables and nuclear are not competing as much as they may seem country-wide, as load capacities across the two tend to have enough difference that they end up supplying different markets. It is important to note that some renewable farms like wind and solar are capable of competing with even the largest nuclear plants in terms of load capacities, like the Bhadla Solar Park in India which boasts an impressive 2245 MW (Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, 2020).

Currently, the majority of baseload renewables such as biomass and hydroelectric do not hold enough market share to compete with nuclear currently. Large scale wind and solar farms like ones that are hastily being put up in China (Xu & Stanway, 2021), who doubled their renewable capacity in 2020, are not widespread yet but will continue to threaten nuclear energies market share as new projects get taken on. Despite capacity increasing worldwide for renewable energy, the efficiency of these energy sources is frequently brought to question. Renewables are dependent on many external factors to produce energy, mainly wind blowing and the sun shining.

This issue of productivity could hinder renewables as a baseload power source since inconsistencies are out of our control. Nuclear, on the other hand, does not share this issue. Planned refuelings, which allow for the proper maintenance and upgrades, are generally the only times in which a nuclear plant stops supplying.

This alone shows why renewables cannot fight alone against fossil fuels and natural gas to produce clean energy. A sufficient, large-scale production must be able to provide baseload power to consumers when renewables might not be able to. As stated earlier, natural gas is clearly taking a foothold as a baseload power supplier, since natural gas plants can produce upwards of 50-60% less CO2 than coal plants (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2014). This is directly lowering nuclear’s market share.

However, emissions from natural gas compared to nuclear power paint a much different story. Nuclear energy produces roughly 7% of the CO2 emissions that natural gas does and only 3% for coal (World Nuclear Association, n.d.). This means that natural gas produces 15 times more CO2 than nuclear and about 30 times more than coal.

This shows that natural gas is clearly not effective enough at reducing carbon emissions and should be seen as a band-aid for a gaping wound. Nuclear and renewables are a more proper remedy for a society seeking carbon neutrality.

Why New Policy in Energy Production is Desired

It is proven that climate change is becoming increasingly threatening and expensive to our planet on a global scale. This is being caused by the burning of fossil fuels, whether it be from energy production, transportation, etc. which will continue to have downstream impacts on human health, the environment, and the global economy (Nunn et al., 2019).

By changing the policy within high emitting economic sectors, we can prepare communities for the change over to reliance on clean energy and incentivize investments into different technologies such as nuclear energy.

Greenhouse gas emissions are the main focus of the Paris Climate Agreement since the emissions experts are calling attention to raise the temperature of the earth’s surface since the carbon dioxide is trapped in our atmosphere (NASA, n.d.).

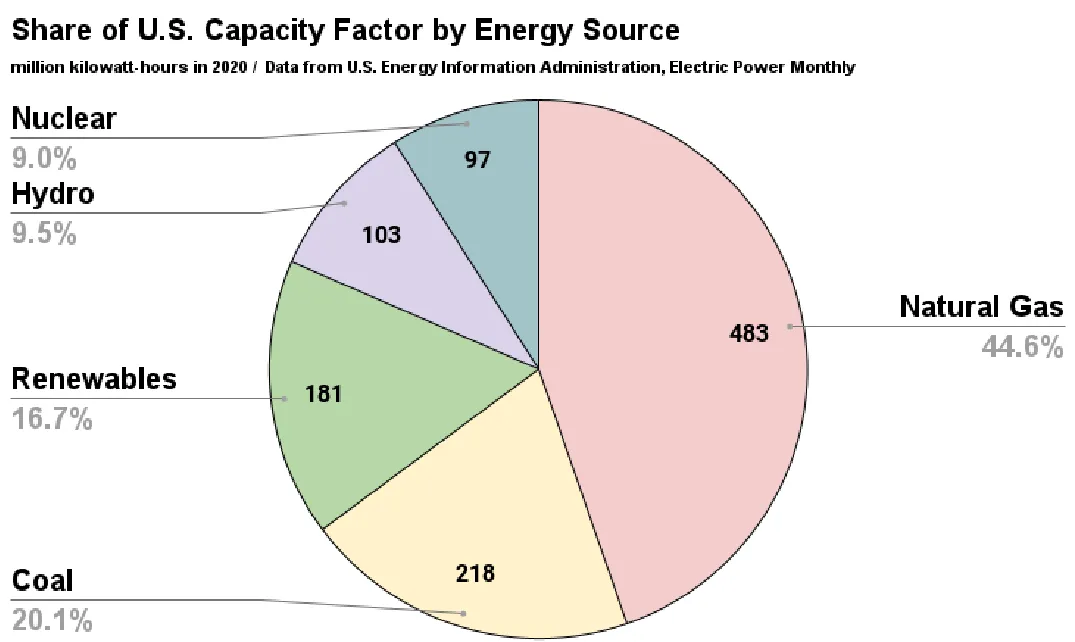

On the chart below, you can see a breakdown of emissions across U.S. economic sectors, with electricity generation taking a fourth of the chart up.

Figure 1.4

Currently, because of these emissions, the sea level increases by 3.4 mm a year, and that number is rising (NASA, 2021). This could lead to large-scale displacement of populations near certain large bodies of water. Effects on precipitation patterns, as well as frost-free seasons, will directly hurt our farmers who vitally produce for the food supply chain here in the U.S. and are estimated to have generated 1.109 Trillion USD for our GDP in 2019 including related industries that farmers support (United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, n.d.).

On top of more droughts and famines due to this, hurricanes will become more deadly and frequent (Knutson, 2021). These issues with the environment are horrendous enough but do not paint the entire picture of how devastating climate change will be to humans.

The effects of climate change don’t just affect the environment, they will directly hurt the overall human health of the world.

According to CDC.gov, “Ground-level ozone (a key component of smog) is associated with many health problems, such as diminished lung function, increased hospital admissions and emergency room visits for asthma, and increases in premature deaths” (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Climate change could clearly hurt the average person’s pocket book since the typical hospital room stay costs around $10k and more pollution increases the average person’s chances of visiting the hospital (Fay, 2021).

The Paris Climate Agreement sought to answer a lot of these problems since accountability can now be held against a government or private business if you fail to prepare and adjust your economy to match the changes that need to be made. The growing need for policy advocating for clean energy production could lead to breakthroughs in the area of transportation and others.

With that in mind, we see how clean electricity is capable of having downstream impacts on the other sectors. These effects won’t be analyzed, rather it is important to point out that clean energy production can lead to further technological developments in other areas outside of energy production.

Electric vehicles, electric home heating, etc. will then, almost, be entirely free of carbon emissions. Thus, decarbonizing the electricity sector through policy change is of major importance in our fastest path to zero and meeting the benchmark set out by the Paris Climate Agreement of limiting the global temperature increase to 1.5℃ to 2℃ above pre-industrial levels in this century (Denchak, 2021). To achieve this, the member countries are aiming to become net carbon emission neutral by 2050 (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015).

Meeting the requirements of the Paris Climate Agreement by limiting the rise in the average global temperature for the 21st century will take many different methods.

The main metric for achieving the slowing rise in average temperature is reducing carbon dioxide emissions from the top emitting economies. A key emitting industry is the electricity generating industry. With clean, carbon-neutral ways of producing electricity for consumption, there will be many downstream effects like the utilization of electric vehicles and heating of buildings that could be powered by a green energy source instead of fossil fuels.

Currently, the common types of green energy sources in this conversation are wind turbines and solar PV panels. However, nuclear should also be a serious part of this discussion because it does have strengths that can supplement renewable energy.

These two, nuclear energy and renewable energy, can work together to help us get to our carbon goals and climate goals steadily and on time.

At this time, nuclear energy has substantially higher capital costs than other methods of electricity production. We will be examining how it currently compares to coal, natural gas, wind turbines, and solar PVs.

Then, we look at two major ways to make nuclear energy cost-competitive in new construction, by increasing the price of carbon and by tax credits. Methodology

Comparing the costs of building new power plants of each type will be done by looking at total capital cost (TCC) and the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE). We will be using the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) formula for calculating LCOE (International Energy Agency, 2020). Since we are mainly interested in making nuclear cost-competitive based on its construction cost, we will look at its TCC where construction cost is the major component of TCC. LCOE will be compared for the purpose of examining the impact of carbon prices on fossil fuel-based energy production.

𝐿𝐶𝑂𝐸 = Σ(𝐶𝑎𝑝𝑖𝑡𝑎𝑙𝑡 + 𝑂&𝑀𝑡 + 𝐹𝑢𝑒𝑙𝑡 + 𝐶𝑎𝑟𝑏𝑜𝑛𝑡 + 𝐷𝑡) *(1+𝑟)−𝑡 Σ𝑀𝑊ℎ (1+𝑟)−𝑡

11 Table 2.1

Variable Name Description

Capitalt Total capital needed at year t.

This includes the materials and labor for the construction of the plant as well as costs to the owner like land usage, operator’s license, and financing of the plant.

O&Mt Operations and Management costs at year t.

This includes running and staffing the plant once it has connected to the grid and is producing electricity.

Fuelt Fuel costs at year t.

This is the price of fuel that is needed to operate the plant.

Carbont Carbon price at year t.

This is for power plants that emit CO2 and is set by the

government or industry the plant operates in.

Dt Decommissioning and waste management costs at year t.

Decommissioning is the ceasing of plant operations and disassembly of equipment at the end of the plant’s life. Waste management includes the storage of waste products or spent fuel resulting from operating the plant.

r Discount rate

MWh MegaWatt hours

Analysis

SWOT Analysis

To start off our analysis, we will look at our SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis of large nuclear plants in the United States. We can see some insight into different aspects of nuclear energy.

The SWOT analysis is frequently done in businesses of all sizes to gauge the company or the market in terms of its strengths and weaknesses and how those can be used to overcome the opportunities and threats that face the firm.

Figure 3.1 By understanding the positives and downsides of nuclear through this lens, applying the correct policy becomes easier if the weaknesses and threats can be identified. Changes in policy within some of these areas have already been identified and pushed for, such as our uranium supply and weapon proliferation (Baranwal, 2020; Ferguson, 2009).

With that in mind, the threat section of the SWOT gets to the bulk of the issues surrounding nuclear and showcases what policies are highly desired in nuclear: safety and cost.

Alternative energy sources, mainly natural gas and renewables, are great threats to nuclear energy since they’re projected to cost less in the foreseeable future (United States Energy Information Agency, 2021).

For nuclear to succeed in the current energy market within the United States, the threats of long-term nuclear waste storage, safety, and the loss of market share to renewables/natural gas must be addressed. While our claims of a lower-cost nuclear market are possible, leaving too much room for firms to cut corners must be highly considered in regulatory practices of energy production.

With the new plant and reactor designs consistently being innovated, nuclear plants of the future must address these issues in a way that saves money in the long run in a safe manner.

Also, the state must regulate efficiently in order to keep firms operating properly and help keep costs low by using streamlined systems to monitor and gauge plants on an individual basis.

Top entrepreneurs have had this same idea for a long time now. From a non-policy standpoint, Elon Musk, who has made large innovations towards clean energy in the transportation industry, recently claimed, “I really think it’s possible to make very, extremely safe nuclear (Clifford, 2021).”

For nuclear energy to make any significant comeback, entrepreneurs like Musk must step up and lead the charge through innovation or the proper backing of the people who can help innovate. While innovations are happening rapidly across all energy sources, nuclear energy specifically could garnish large results if more tech-driven, unconventional businesses like the ones founded by Musk thrust

new ideas into the aging industry of large-scale nuclear production. With America’s finest business talent leading the charge, nuclear energy could have a large comeback if the threats listed in this analysis are addressed swiftly.

Age of Current Plants

Figure 3.2

Data taken from https://pris.iaea.org/PRIS/CountryStatistics/CountryDetails.aspx?current=US

As shown in Figure 3.2, the variable represented on the X-axis as AGE is from the first year construction began on the plant, the average nuclear plant since construction began is reaching past the age of 50 already, with the mean age being 50.5 years.

For reference, 43 years before 2021 was 1978, 53 years ago was 1968, and 65 years ago was 1956.

Looking at a plant from the age it began construction is relevant since liabilities towards the owners begin to occur despite no production of energy taking place yet.

With this in mind, the government and industry need to begin preparing plants for reinvestments and lifetime extensions or to be slated for decommissioning.

In the United States, licensing is given for 40 years although most plants have already renewed their license for the standard 60 years, which is why it is time to begin preparation for these plant’s futures.

Plants must pass rigorous examinations from the NRC, which include full inspections, environmental impact reviews, analysis of aging effects, and overall performance evaluations (Nuclear Energy Institute, n.d.).

To back this claim, energy.gov reports, “To date, 20 reactors, representing more than a fifth of the nation’s fleet, are planning or intending to operate up to 80 years (United States Department of Energy, 2021).”

The lifetime extensions these plants are receiving could prove to be beneficial to investors looking to hold assets long term. Closing down a nuclear plant prematurely or altogether could lead to more harmful effects on the environment and it could stop the stakeholder’s chances of profiting or maximizing current profits (Clemmer et al., 2018).

As a plant continues to get upgraded over time, the cost is significantly lower compared to initial capital investment, so it can be expected that its output and thus revenue increases. This is a massive strength towards nuclear’s case for increasing its share within the energy mix. Nuclear energy is proven as a long-term reliable energy option that can be deployed for large-scale projects (World Nuclear Association, n.d.).

On the flip side, when a nuclear plant does decide to shut down and go into the decommissioning phase of the life-cycle, the plant has likely already been online for 50+ years.

Decommissioning due to aging has a relatively small impact on the total overall cost of a plant compared to the overall budget of a plant. Some estimates range the total cost of decommissioning making up 9-15% of the initial capital cost of a nuclear plant (World Nuclear Association, 2020).

Regulations

Nuclear regulations following the Three Mile Island accident affected the construction of new plants starting in 1980 with the NRC Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1980 and Reorganization Plan No. 1 of 1980 (Holt, 2015).

This led to an increase in construction time as new guidelines for structures on sites were increased which required additional layers of safety and protection to be put into place (Cohen, 1990).

More time was spent in the planning phases as designs had to be altered by planning professionals. Bernard L Cohen states, “according to the United Engineers estimates, the time from project initiation to groundbreaking was 16 months in 1967, 32 months in 1972, and 54 months in 1980.”

Along with increases in inflation, pre-production planning during the 1980s greatly increased the cost of labor during the construction of new nuclear plants. Table 3.3 is a breakdown of how the NRC structures the regulatory practices of the agency and the effects they have on the governed bodies.

Table 3.3

- Regulations and Guidance ● Rulemaking ● Guidance Development ● Communication & Standards

- Licensing, Decommissioning, and Certification ● New Licensing ● Planning and assisting in decommissioning ● Certification to allow the production of certain materials or practices

- Oversight ● Inspection ● Assessment of efficiency and overall performance ● Enforcement/Penalties ● Allegations, investigations, and rapid incident response

- Operational Experience ● Evaluation of operating experience given a scenario or event ● Creating solutions for generic issues

- Support for Decisions ● Research into new systems of regulation ● Holding hearings on regulation decisions with parties affected ● Permitting and obtaining independent reviews to back decisions Retrieved from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission at https://www.nrc.gov/about-nrc/regulatory.html For the state to regulate effectively, the policy that is put forward for nuclear must be flexible yet thorough in its design. The accident that occurred at Three Mile Island, a crisis in which the release of radioactivity “did not seriously contaminate the surrounding area with radioactive isotopes (University of California Press, n.d.).”

This led the way for a policy that is counterintuitive towards the production of energy using nuclear power. Other forms of policy have also come into fruition in recent years.

There are a few new policies put into effect within the past couple of years and a few in the making are currently being discussed. They are ONWARDS and a new infrastructure plan that was passed by the US Senate and is being voted on in the US House of Representatives at the time of writing. ONWARDS stands for Optimizing Nuclear Waste and Advanced Reactor Disposal systems. It provides $40 million of funding towards research in advanced nuclear reactors and reducing the spent fuel waste.

The ONWARDS program is a part of ARPA-E, the Advanced Research Projects Agency - Energy branch of the US Department of Energy. The infrastructure bill that was recently passed by the Senate has some sections providing funding for nuclear research and operations. They are found in Sec. 40321-40323 and Sec. 41002. Funding for nuclear research includes research into micro and small modular nuclear reactors and advanced nuclear reactor demonstrations or test runs.

There are funds made available, $6 billion according to Catherine Morehouse for Utility Dive, for nuclear plants that might cease operations due to economic hardship and will be awarded funds over a 4 year period (Morehouse, 2021).

New plants or projects that may come from renewed interest in nuclear energy could benefit greatly from more lenient regulations. While safety is one of the utmost priorities for any business, regulations from the NRC are expensive and bog down the production process.

The process in the United States to obtain a license is not difficult but can take time and cost a lot, which leads to the overruns that increase the LCOE value of a plant.

Construction Time of New Nuclear Plants

Figure 3.4

In Figure 3.4, we notice that there is already a steady increase in TCC prior to the Three Mile Incident in 6. Looking at the data from the EIA and decommissioningcollaborative.org, we obtained a rough TCC that likely includes initial capital cost for the construction and refurbishment over the years to improve and maintain plant operation.

The data pulled is for a one reactor plant and some of the years had multiple plants begin construction which we averaged the TCC and the years from construction start to grid connection. Grid connection is taken to mean that the plant has begun commercial operation. In Figure 3.5, it shows that with each new construction there is an increase in rated output. Like in Figure 3.4, for years that had multiple plants begin construction, the rated output was averaged.

The increase in rated output is likely from changes and improvements in reactor technology which should coincide with the increase in price and time to commercial operation.

These reactors are likely first-of-a-kind (FOAK) and would also contribute to the dramatic increase in TCC. The designers and engineers have to begin the process of learning which new practices to adopt for the new technology being implemented when working with FOAK.

However, in subsequent builds, the learning obtained from FOAK should translate to a reduction in materials and time needed for construction. Instead, we see that the time from construction start to grid connection also overlaps with the Three Mile Island reactor no. 2 meltdown. Looking over the entries on PRIS and the EIA, we have not seen any new nuclear plant constructions after the Three Mile Island.

Figure 3.5

Construction time of nuclear power plants was relatively quick in the 1960s when the first plants were being built. Over time, with more sophisticated reactors and equipment being used, the overall construction time slowly increased.

This became more pronounced after the Three Mile Island accident.

The backlash against the nuclear industry was fierce and the federal government needed to enact policies to safeguard against any problems that may arise during the operation of a nuclear plant in the future. Because of the increase in the number of safety measures that were being implemented by Congress and to be enforced by the NRC, it forced nuclear plant owners to reevaluate the plant designs to accommodate these new safety features. Doing so, increased the amount of time required for the construction of new plants and reactors greatly as shown in Figure 3.4. With the increase in construction time, the costs of professional labor like engineers and management also increased.

From an MIT report, Department of Energy (DOE) researchers discovered that construction costs of plants increased mostly from indirect costs - costs that are related to engineering and designing, on-site supervision, and facilities needed during the building process (Stauffer, 2020).

These indirect costs total about 72% of increases in cost from 1976-1987 while the remainder was mostly attributed to three physical components: the steam supply system, the turbine generator, and the containment building. The DOE researchers discovered that based on cost estimations for the construction of containment buildings, they were able to discern that most of the cost increases were based on more materials being used and a drop in labor productivity.

Labor productivity in the construction industry had dropped overall from 1976-2017 but construction in the nuclear energy industry, in particular, had lowered an ever greater amount. The DOE also discovered there was a discrepancy between projections and actual material usage that contributed significantly to the cost overruns. Large, capital intensive projects suffer hard when labor productivity drops, which highlights why policy changes within massive capital projects need to be considered.

Capital Costs

Capital costs consist of raw materials and labor needed for new plant construction, land procurement, operator license, decommissioning fund, and financing/interest rate on loans for the project. Within nuclear energy from a global standpoint, capital costs are the most intensive and most likely to cause overrun. This means that tightly controlled markets will benefit from putting up nuclear plants since funding and construction are streamlined. Table 3.6 Figure 3.7

Table 3.6 is the numerical representation of data on total capital costs of different plant types in USD from a 2020 report for the EIA by Sargent & Lundy as well as the rated output in MW for each plant type. Figure 3.7 is a graphical representation that gives us a better look at how the costs compare with each other. The EIA report did not have a look at nuclear long-term operation plants, which are plants that are upgraded and run beyond their original lifecycles, so it was not included.

What is included is coal without and with a carbon capture system installed, natural gas with and without a carbon capture system (CCS), advanced nuclear light water reactor, nuclear small modular reactor system, offshore and onshore wind, solar PV panels, and solar PV with a battery storage solution. These are all electricity generation facilities that are considered utility-scale.

This means that they are to be operated by a utility company and sell their electricity produced on the market, as opposed to selling at a wholesale price to a utility company to transfer the electricity.

The data gathered from the EIA shows a nuclear LWR is significantly more costly in total capital costs for new construction in comparison with all other types of electricity generation. However, when we look at Figure 3.8, the USD/kW of nuclear LWR is much closer to offshore wind and coal with a 90% CCS.

Also, the expected plant operating lifetimes differ with nuclear LWR needing minor investments in upkeep and license extensions to continue running for more years.

From an economic point of view, the real reason nuclear is not more widespread is because of its price tag. Using the above table and graph with data from the EIA shows the striking difference in total capital costs to build a new LWR nuclear power plant. Investors could be put off by issues with nuclear waste 21 and radiation, as for financial purposes they care more about return on investment (ROI), and currently nuclear is one of the most expensive energy sources around. Additionally, the majority of nuclear plants in the US are approaching the end of their lifetimes.

Investment in new large-scale nuclear plants is dropping because of its initial price. So instead of building new nuclear plants, cheaper alternatives are chosen, either natural gas plants or renewable energy plants.

Natural gas is chosen over coal because the price of natural gas is currently low and it doesn’t emit as many harmful pollutants as coal (United States Energy Information Agency, 2021).

However, renewables are not yet able to sustain energy output to cover base load demands, so ultimately, natural gas plants will be chosen to be built. Therefore, in order for nuclear power to become more widespread as a means of producing electricity that does not produce greenhouse gas emissions, it must become more economically competitive with its base load competitors, coal and natural gas. Figure 3.8

Figure 3.8: EIA notes that for Total Overnight Costs:” Overnight capital cost includes contingency factors and excludes regional multipliers(except as noted for wind and solar PV) and learning effects. Interest charges are also excluded. The capital costs represent current costs for plants that would come online in 2021.

The total overnight cost for wind and solar PV technologies in the table is the average input value across all 25 electricity market regions, as weighted by the respective capacity of that type installed during 2019 in each region to account for the substantial regional variation in wind and solar costs.

The input value used for onshore wind in AEO2021 was $1,268 per kilowatt (kW), and for solar PV with tracking it was $1,232/kW, which represents the cost of building a plant excluding regional factors. Region-specific factors contributing to the substantial regional variation in cost include differences in typical project size across regions, accessibility of resources, and variation in labor and other construction costs throughout the country.”

According to Figure 3.8, the data are projections done by the EIA to estimate what the overnight cost of a power plant could be based on the source. We see that overnight costs in terms of $/kW are higher in nuclear (LWR, SMR) compared to other energy technologies.

This table is one of the main reasons nuclear is not being considered as a long-term viable option to support our growing energy grid since the cost of construction is simply too high. We see how production can impact projected $/kW. Despite LWR technology being some of the most expensive in construction costs alone, it is unmatched in terms of what is capable with size and output.

It is important to compare costs in terms of output as well. The opportunity cost of an energy project is dependent on the amount of output you are expecting, therefore some projects might require a nuclear LWR since it can provide baseload power. We will now discuss why that is important within the next section.

Comparing LCOE of different plant types

Using the IEA’s online LCOE calculator, we will be looking at the different power plant types in the following graphs. By making adjustments to the carbon price in Figures 3.10-3.12, we notice that changes in carbon price do not affect the LCOE of nuclear and renewable energy types. It makes sense because they do not emit CO2 while operating.

For fossil fuel plants, the plants that have carbon capture and sequestration systems (CCUS) are not as affected by the changes in carbon price as fossil fuel plants that do not have the CCUS.

Nuclear plants are designed to have an operating lifespan of 40 years. LTO, long-term operation, is beyond that. In the U.S. 20-year extensions to operating licenses are given out when operators of plants have applied for them and passed the necessary checks (United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2020). But, what is shown in the graphs made from data taken from the IEA, are a category for LTO with a 10-year duration and LTO with a 20-year duration.

There would be additional capital costs with LTO because parts would need to be replaced and upgraded for the continued functioning of the plant beyond the original lifespan and specifications.

The extra capital costs would be much smaller compared to a new build because most of the existing structures and parts would not need to be replaced.

Table 3.9

Carbon price Reasoning

$0 Chosen to observe the effects of a lax approach to carbon emissions $30 IEA’s default price they observed globally $50 Roughly the price set by Biden Administration $100 Chosen to observe the effects of a more aggressive approach to carbon emissions In Table 3.9, we offer some explanations on the carbon prices chosen that are represented in Figures 3.10-3.12. A low carbon price of $0-30 is beneficial or advantageous to fossil fuel power plants that don’t have a CCS in regards to how it affects the LCOE of new plant construction.

In comparison to a new nuclear LWR construction, Gas CCGT without CCS and low carbon price is more cost competitive at a 3% discount rate. It takes a $50 or more carbon price and a discount rate of 3% before nuclear LWR becomes more cost competitive than Gas without CCS. Gas with CCS becomes cost competitive with 23 nuclear LWR when discount rates are 7% or higher. Also, if the US chooses to pursue an aggressive approach to tackling its climate goals, it would set carbon prices higher.

This would incentivize fossil fuel burning plants’ owners to invest in CCS. If potential investors in power generating plants have to choose between a natural gas plant with a CCS or between a nuclear LWR plant, they may find a nuclear LWR more appealing in this situation.

In the IEA report on discount rates, ”…a 3% discount rate corresponds approximately to the social cost of capital, a 7% discount rate corresponds approximately to the capital cost of a large utility in a deregulated or restructured market, and a 10% discount rate corresponds approximately to the cost of capital in an environment with relatively higher risks (International Energy Agency, 2020).” They go on to say that, “Nominal discount rates would be higher, reflecting inflation.”

It’s also mentioned that there would likely be differences in discount rates between different plant types. This is likely due to the perceived risk involved in building a new power plant of any given type and how long the construction process is which leads to how soon the plant begins operation. The sooner the plant is able to begin operating, the sooner it can generate revenue.

New nuclear light water reactor (LWR) plant constructions are cost-competitive when the discount rate is low and the carbon price is high as shown in Figure 3.10.

But, when discount rates are high, at 10% in Figure 3.12, nuclear LWR is no longer competitive with its current alternatives, such as natural gas with a CCUS, solar PV, and wind.

As explained previously, the discount rates won’t be the same between different plant types. This can be attributed to a variety of reasons that consider the lender’s stance on a particular energy type, the lender’s stance on global climate policy, which forecasting model the investor aligns with regarding the revenue schedule and ROI of a particular energy type, energy market trends, and availability of government funding among many other reasons.

Figure 3.10 Figure 3.11 Figure 3.12

Cap and Trade

Not many regions in the US have a cap and trade system for carbon emissions. California is currently the only individual state with a fully functioning system and Washington state has one in development.

The RGGI (Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative) is an agreement between 11 states, as of January 2021, in the northeastern part of the US (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia) with a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% of 2020 levels by the year 2030 (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, n.d.). This market approach is considered better for dealing with CO2 emissions because it is more flexible for firms by rewarding good behavior.

Firms that are emitting below their allowances can sell their excess allowances to firms that are emitting more than the number of allowances they currently own. In California’s case, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) gives out a certain number of free allowances to firms and has set the auction price of additional allowances to about $19 as of May 2021 and as shown in Table 3.15 (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, n.d.).

One allowance is equal to one metric ton of carbon equivalent emissions. Currently, CARB has a self-ratcheting system where a set amount of allowances are auctioned off in a given period and the ones that remain unsold for a certain period are taken off the market.

CARB is also allowing additional allowances to be available for trade beyond the initial allotment set at the current going price at a higher price (California Air Resources Board, n.d.).

Revenue generated from this program allows California to invest in more green projects. These projects include further research for green energy types, promotion of low and no carbon-emitting forms of transportation, and sustainable agriculture. California has taken some of the externalized costs of energy generation and industry and reinvested it in various ways to help benefit the citizens of the state. Having a low floor on a carbon price of $19 does not make nuclear as attractive of an option going by the data pulled from the IEA calculator graphed in the section discussing LCOE. This carbon price would put fossil fuel plants at slightly below the $30 mark in Figures 3.10-3.12.

Nuclear power plants do take a considerable amount of time to construct and would only become more cost-competitive if plants continue to operate beyond their originally scheduled lifetimes as shown in the difference between Nuclear LWR and Nuclear LTO. Table 3.13

Figure 3.14

Carbon Capture and Storage System

One way for fossil fuel plants to help internalize the costs of the burden on the society they produce would be through a carbon capture system. A carbon capture system is built onto existing plants or built-in during new plant construction.

Carbon capture systems can raise a plant LCOE value quite drastically but we feel as if this will be the best way for coal and/or natural gas plants to begin manifesting the negative externalities placed onto society, this is backed by our graphics since fossil fuel plants with carbon capture and storage are less impacted by increased carbon prices.

The question at hand remains simple: will we accept increased rates of medical bills, disease, and death from pollution with regards to coal and fossil fuel production? Or will we say that enough is enough, and force fossil fuel firms to pay for the economic damages they cause in a wide variety of areas?

Not only will a carbon capture system help with this but it will also reduce the amount of new CO2 into the atmosphere. Carbon capture would be mostly for coal because of the number of emissions per kWh produced from burning coal. This won’t always be the case though, as seen earlier in Figures 1.2 and 1.3, natural gas is taking a stronghold in the United States as the key supplier of energy and the pandemic seemed to solidify that natural gas is becoming increasingly engrossing to key energy investors economically due to its low cost for capital, fewer emissions compared to other fossil fuel sources and abundance of fuel. Specifically, in the United States, natural gas production is largely spurred on by federal government incentives such as tax credits and subsidization.

To coincide with green energy sources, natural gas producers must be willing to internalize their harmful costs on society with carbon capture. This will spur debate since a large perk to natural gas in its current state is the low barrier of entry compared to other energy sources.

Overall, a policy requiring a carbon capture system can internalize some of the costs/damages that have already been done to society to the firms that caused it and possibly drive investors towards other energy sources such as nuclear. We believe the fastest path to zero must involve carbon capture technology since it could rapidly reduce the number of emissions per year while opening the doors for further development of clean energy sources. On top of this, a carbon capture and storage system will allow for nuclear to become more cost-competitive since capital-intensive projects tend to incur much larger costs.

Financing New Nuclear Construction Projects

Starting up and financing a new nuclear plant can be difficult for a number of reasons. High capital costs and government vetting processes at the beginning of a plant’s life cycle can feel like lighting money on fire for investors, since the bulk of the cost will be upfront, and revenue is not expected until production comes online. In the United States, the responsibility of securing the correct investment for the job falls solely on the plant’s operating parties, which may be more than one company to spread liability. By spreading the risk of the financing between multiple parties an operating company may feel more comfortable with their investment since profit and losses will be shared.

The nuclear market is difficult to break into within the United States since the government will only allow certain companies to build new plants.

Companies must show a track record of being safe and efficient, as well as having a clear working plan for waste and decommissioning before any bank or government will allow a plant to go up. As of right now, new nuclear construction projects are not financially viable since the construction process of a plant takes far too long and costs too much.

The federal government can solve both of these issues by honing in and adjusting the regulatory practices or bodies that govern nuclear plants to more accurately reflect the current global nuclear market.

As of right now, the United States is falling behind other superpowers because of this, notably China. A more centralized government allows for more effective and reliable financing compared to an open market. France, which is discussed in depth later, is a great example of how a liberalized democracy can centralize the energy economy for the sake of efficiency, making financing and any large-scale infrastructure project easier.

This claim is backed by the fact that France builds PWRs faster than the world average (Carajilescov & Moreira, 2011).

While the open market seeks to lower monetary prices using competition, economic analysis of energy production highlights how the social cost of carbon outweighs the gains that the open market seeks. This is a fundamental flaw within the philosophy of American energy production. Politics, unfortunately, outweigh economics at the end of the day and the American political system believes in maximizing stockholder shares, including energy businesses, which gets inhibited when you mention the social cost of carbon emissions. 30 Decommissioning Decommissioning is the process of deciding what should be done with a power generation station at the end of its operating life. Normally, plant owners are required to set aside funds for the plant’s eventual decommissioning. For nuclear plants, the amount is relatively small compared to the construction costs portion of total capital costs. From the IEA’s 2020 LCOE calculations dataset, this ranges from $0.39/MWh for a 1100MW nuclear LWR with 3% discount rate to to $0.01/MWh for the same output plant with a 10% discount rate (International Energy Agency, 2020). Compared to the construction costs of $22.58/MWh for a 3% discount rate and $77.61/MWh for a 10% discount rate. Plant decommissioning can take on many forms. What laypeople may think of decommissioning is the plant site will be completely disassembled and the land restored to how it was before the plant was constructed. However, there are actually many different kinds and levels of decommissioning. In the report on the decommissioning of power plants, other than nuclear, in the US from the Resources for the Future (RFF), this is made much clearer (Raimi, 2017). Figure 3.15 Source: Resources for the Future (2017) According to Figure 3.15, only the third branch under “Decommission” fulfills what a layperson would normally consider decommissioning. This is when all waste products have to be removed from the plant site and all evidence of the previously existing power plant has to be removed. The land has to be rehabilitated and free from any contaminants that may have been released from the power plant into the 31 surrounding environment. Once all of this work is done, and it is supposed to be the responsibility of the owner of the power plant, the land and environment is inspected to ensure it will be suitable for spaces where people can build homes. But, the complete decommissioning of a plant is not always economically viable for owners, so the land is not converted back into the “greenfield” or back to pre-plant conditions. For nuclear plants, being built a ways outside of metro areas, this can mean land that used to be classified as wilderness. More often, the land will be repurposed to a state where the land is remediated well enough that it can be repurposed for industrial use. This state is called a “brownfield,” from Figure 3.15. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) requires that nuclear plant sites being decommissioned have their license terminated and for the land to either be released for unrestricted use or to be released for restricted use (United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 2021). What the NRC calls “unrestricted use” would be similar to “greenfield” from the RFF.

The plant site can have a portion of the space housing the dry cask storage of spent fuel and reactor parts that have to be maintained by the plant owner. The rest of the site is available for anyone to use or develop in the “unrestricted use” scenario. An example of a plant decommissioning that falls under “unrestricted use” is the Connecticut Yankee nuclear power plant at Haddam Neck, Connecticut (Connecticut Yankee, n.d.). They were able to remove as much of the existing plant structure as possible except for the spent fuel and high-level radioactive reactor parts that are stored in large cement dry casks. This is probably one of the best examples of decommissioning a nuclear power plant to revert the land back to pre-nuclear plant use as there is with regards to what the owner of the plant is able to accomplish. Connecticut Yankee Atomic Power Company, the investor group that owns the plant, removed all of the buildings and infrastructure as required by NRC guidelines. This consists of containment buildings, offices, parking lots, pumps, and pipes, etc. The dry casks of spent fuel and reactor parts are still on site and have to be monitored by Connecticut Yankee Atomic Power Company because they claim that the DOE has not retrieved them as outlined in their agreement. Around 38 acres of land has been turned over to the US Fish and Wildlife Service along the Salmon River to be used as a wildlife refuge. Subsidies & Investments To start off, we would like to discuss some comparisons amongst different subsidy types. Subsidies can take on many different forms, often being split into direct, indirect, and R&D subsidies. For energy production, there are mainly direct and R&D subsidies that can take on the form of many different schemes, with the goal being to make technology more competitive and to adjust the price and cost of the commodity. As you can see below in Figure 3.16, this is a basic breakdown of the subsidies nuclear has received from 1950 to 2016. Since nuclear is heavily dependent on the technology it works off of, R&D has been substantially invested towards it. The thorough safety designs, fail-safe features, employee training, and a lot more has been directly impacted due to the massive amounts of research put towards large-scale reactors, the industry owes these subsidies a lot for the growth and sustainability of the market. 32 Figure 3.16 With that being said, the subsidies are not enough. Nuclear energy has received 8% of all federal incentives from 1950-2016, compared to oil’s 40% and renewables’ 16%, which totals roughly a billion dollars or 80 million for just nuclear at 8% (World Nuclear Association, 2018). According to the Environment and Energy Study Institute, direct subsidies aimed towards fossil fuels result in $20 Billion per year with a breakdown of roughly 20% for coal and the other 80% for crude oil and natural gas (Coleman & Dietz, 2019). This showcases how the citizens of the United States, who largely fund these subsidies, need to make their voices heard if any significant change is going to happen. With the ushering in of the Biden Administration, new or increasing subsidies towards fossil fuels are unlikely in the future but that does not change how the current tax code in the United States is laid out, which seeks to directly benefit the fossil fuel industry in its current state. Just as recently as 2017, President Trump’s tax plan upheld 26 U.S. Code § 263, related to intangible drilling deductions, states that: “…which granted the option to deduct as expenses intangible drilling and development costs in the case of oil and gas wells and which were recognized and approved by the Congress (Govinfo, 2012)”. These parts of the U.S. tax code have taken hundreds of millions of dollars in lobbying to keep up, which directly benefits those involved in fossil fuel production (OpenSecrets.org, 2021).

On top of that, a massive tool used by governments to subsidize the production of commodities is the PTC or Production Tax Credit. This form of subsidy helps with new plants implementing state-of-the-art technology since it can raise some of the risk, as well as older plants since production numbers have likely stabilized and will be expected to grow alongside the reactor upgrades.

An investor who can forecast costs with a long-term PTC in mind will feel more comfortable with the construction of a plant since the growth and upgrading of the plant could mean more money saved per MWh of electricity produced. This could also potentially help with large plants since the production numbers of nuclear plants are high in volume and efficient compared to other energy sources (United States Department of Energy, 2021).

As of 2021, the current political climate around PTC in the US is shifting, with Democrat lawmakers being recently pressured by the industry to implement a PTC (PTC Letter of Support, 2021). Currently, in the United States, nuclear plants receive “1.8 c/kWh from the first 6000 MWe of new-generation nuclear plants in the first eight years of operation (World Nuclear Association, 2020).” This small credit for the first 6000 MWe simply is not enough to make nuclear competitive with other energy sources. The first problem is that nuclear’s costs mainly come from construction and capital costs, which cause a high LCOE value.

The production of nuclear energy can be unprofitable in the beginning, which is what this credit addresses, but overall it misses the mark on being influential towards lowering the LCOE, which will be an incentive to investors to build more nuclear plants, which is where a bulk of the risk lies. Secondly, an investment tax credit (ITC) could also be useful towards upgrades and new plants. An investment tax credit is exactly what it sounds like, a credit for investing within a certain technology. This type of policy has been proposed for nuclear plants in the past in the House and is considered being used to help the energy market as a whole with regards to the distribution of energy (Galford, 2019; Ernst & Young, 2021). By giving an ITC to nuclear energy and supporting industries like utility companies, the government could allow existing plants to upgrade to the sufficient parts that they need and incentivize new investments towards nuclear construction. This addresses our issue with PTC, as well as increasing the number of jobs provided to the economy if new construction or upgrades were to begin. PTCs would not be applicable to new plants in construction because they are a credit given based on the amount of electricity generated. Also, new nuclear plants take many years to be built, with the average plant between 1976-2009 was roughly 7.7 years (Carajilescov, Moreira, 2011).

Technology & Government Involvement

Some technologies that may be subsidized by an ITC are SMRs or Small Modular Reactors, which can be produced in factories and deployed on a smaller scale than traditional nuclear reactors with more safety features. This allows for full containment and analysis of the systems individually, which are then created with the whole project in mind. The economies of scale found in large reactors are traded off in SMRs for quick deployment times and hopefully, faster learning rates, which are gauged by capital cost per MW installed and have been a long-time issue for nuclear production.

SMRs solve a huge issue within the economics of nuclear energy production since they are cheaper to produce capital-wise and can be properly tailored to meet the owner’s (or consumer’s) specific demands. New reactors are being designed to adjust output levels based on demand and reactors that use new types of coolant including molten salt and liquid metal can be subsidized as well.

Only the best and most innovative technologies should be considered for an ITC and the government should deeply analyze which technologies will benefit society the most economically and decide from there.

On top of subsidies towards new technologies, the United States could benefit from the government entering cost-sharing agreements with nuclear construction or start-up projects. Similar to France, this would spread liability away from the owners who already risk a lot to provide supply.

This could be done through the expansion of programs that are already in place, such as the Gateway for Accelerated Innovation in Nuclear (GAIN) from the DOE, which looks to assist start-ups in commercializing their nuclear technology. Contracts in the form of federal power purchase agreements could be offered through DOE programs, then auctioned out and awarded to companies that have the best performance in terms of production and safety, guaranteeing a baseline cash flow for the operating company on any specific project.

Government market entrance into the utility sector via capital investment or subsidy could increase revenue for nuclear plants since electricity is currently sold at wholesale prices to utility companies then distributed to consumers in the U.S.

The government could buy electricity at its current market price for utility purposes then distribute at a loss which is passed onto taxpayers. Another way that avoids government competition in the private market would be to subsidize nuclear production firms for the profit which is lost when electricity is sold at wholesale prices to private utility companies.

All of these are great ways to lower the barrier of entry to new firms with lower capital budgets and showcase how there are multiple ways to drive costs down for those already in the market.

As mentioned earlier, research and development towards safer and more efficient nuclear technology through non-profits and universities is highly prevalent in the United States.

The technology involved in nuclear energy is highly sensitive to accidents and robust knowledge of the systems which are employed in construction and production by the operating company are vital towards building a healthy nuclear market. Investing in R&D allows a deeper understanding of these systems, thus allowing operators to handle things safely and correctly when accidents occur. While the government needs to continue its surge of large investments towards R&D in nuclear, other subsidies which address market competitiveness need to be brought to the table quickly if nuclear wants to remain competitive to natural gas and renewables.

Comparison Across International Nuclear Markets

France

Overview

Within the French energy economy, nuclear is the dominant energy source by quite some amount. Nuclear energy within France accounts for the majority of the electricity that is produced.

Because of this, France has become the largest exporter in the world of electricity.

According to the World Nuclear Association, “Over the last decade France has exported up to 70 TWh net each year. In 2018 exports were principally to Italy, Spain, the UK, Germany, Switzerland and Luxembourg” (World Nuclear Association, 2021). Having a clean energy baseload power source which is led by the government has had a significant impact on France’s energy market and the overall economy, which is showcased by these export numbers.

About 90% of France’s electricity generation comes from low emission sources such as nuclear and renewables. In terms of developed economies, France should be seen as a leader in how a government-led energy program mixed with the private market can become independent and reliant on clean energy. This has led France to become one of the better-developed countries in terms of CO2 emissions per capita (Baude et al., 2020).

Overall, France has been a leader in the world in terms of total share and total production of energy produced from nuclear, this has been achieved by numerous systems, including how France is one of the only countries which seeks non-domestic uranium mining development as well as a combination of private and large public investment (Nuclear Energy Institute, 2021; Nuclear Energy Agency & International Atomic Energy Agency, 2020). Despite this, French citizens are not all favorable of new nuclear sites and the United States citizen base is much more excited about the potential of new nuclear projects (Schneider, 2008)

Construction & Financial Policy

As mentioned above, France’s energy sector is a mix of private and public funding. EDF, the largest state-run utility and energy provider for nuclear power in France, cooperates and combines with the public market frequently on projects, leading to clashes between EDF representatives, government officials, politicians, and other big businesses involved in energy production.

Although, in recent times, France has begun to pump the brakes on new nuclear projects and plans on cutting back its total share of nuclear energy production down to 50%, which is quite a drastic reduction that you can picture by looking at Figure 4.1 below (World Nuclear Association, 2021).

In 2014, the French government passed a new policy by the National Assembly and then the Senate titled the “Energy Transition for Green Growth” bill. Within this bill, we see a shift in strategy for France’s energy mix that is more reliant on renewable energy and propose the reduction of nuclear capacity as stated above. Originally, France looked to close enough nuclear plants to hit that 50% benchmark by 2025 but this has been pushed back to 2035 with an update to the national energy policy coming in 2018. Despite this, the building of new nuclear plants is still considered an option in the bill and seems to be getting more attention in 2018.

France is likely always going to keep building new plants as an option, due to their high degree of standardization towards PWR designs. On top of this, nuclear plants in France are rarely discussed amongst politicians and fall outside the discussion within elections, despite the importance nuclear has to the country.

The issue of nuclear power in France is predominantly decided by a group of industrial engineers and technocrats who look to push energy policy without the political debates that come along with it, called the Corps des Mines (Schneider, 2008).

This is explained by the fact that the governing body of the Corps des Mines, the General Mining Council, is controlled by the French Minister of Industry. The ministry of this body may change, but the corporations who support it will not. Because of this, France has an edge on long-term construction projects and decision-making with nuclear since politics are left to the side and the focus is on the stable, long-term policy.

This draws a stark contrast to the United States, where energy policy is dictated by who is currently in power and is more likely to incur sweeping changes in favor of withholding a democratic system across economic industries.

New construction of nuclear plants in France will only happen if it continues to be economically viable, which is a difficult parameter to forecast for any project.

According to Reuters, who reported on new proposed plants that may be considered for construction by the French government, “French power utility EDF estimates it would cost at least 46 billion euros ($51 billion) to build six of its latest generation EPR nuclear reactors if the government decides to build them.

Each reactor would cost 7.5 billion to 7.8 billion euros, based on building the reactors in pairs with financing over about 20 years (Thomas, 2019).” These cost estimates seem about comparable to what a U.S. company would face when constructing a new plant, although it is difficult to say since there are many variables that go into constructing a new plant and the subsidization systems are different.

Whether or not these new plants will be economically viable if they are ever put up has to do a lot with these variables. Cost overruns can occur to any construction site at any time, for a magnitude of reasons.

These are rarely planned for since they are highly unexpected and at times can cause damage to the economic viability of a project.

Despite these occurrences which can happen at any plant, France has many fall back options due to the high degree of standardization amongst designs and effectiveness of issuing policy

As of right now, France’s future for nuclear energy is highly uncertain. Plant’s are being shut down, that is for certain, but when and how is still up for debate. Alongside this, the debate rages on for what will replace that vital clean energy and how it will get accomplished.

As of right now, the French governmentis calling on itself and the private sector to weigh the laid out options rationally and scientifically. France looks to continue support for both nuclear and renewables, but to what degree is left to be seen.

Comparison to the United States

Figure 4.1

Figure 4.2 As described earlier, within 2019 France’s dependency on nuclear energy as a baseload power source and significant interest in renewables is clear, while the United States’ dependency on natural gas and coal is evident based on the distribution of the shares, with the two totaling 62.3% of the graph. It is important to note that these shares may be slightly off since not all power sources are considered, just ones that we felt show significant proportions above 0.5%. With that in mind, when comparing the two charts next to each other, nuclear energy in France holds the largest overall share of nuclear production, with it clearly being the dominant power source there. Hydropower generation is also a notable form of production in France, with it taking the largest proportion of technology considered renewable, opposite of many developed countries who have begun industrializing wind and solar farms mainly. Most interestingly about France could possibly be what is not on the graph, as France has ended coal production entirely in recent years (Enerdata, 2021).

The United States has a unique, diverse spread of power sources with natural gas generating the most electricity in 7. The United States is also heavily reliant on fossil fuel energy sources (coal and natural gas).

France on the other hand generates almost 90% of their energy from clean sources (nuclear, hydro, solar PV). The stark differences between these two countries’ energy mixes can be explained by a multitude of reasons, the main reason boils down to uncertainty. In both situations, the energy crisis and oil shocks of the 1970s contributed significantly to the make-up of these pie charts (Yale University, n.d.).